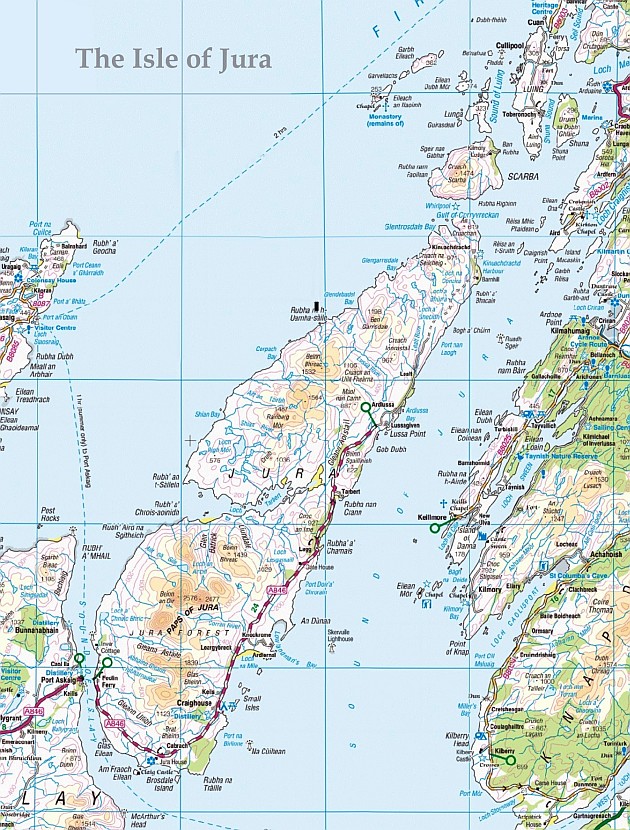

The one road south to north on Jura roughly follows the line of the east coast. Fifty minutes of driving around some interesting bends brought us to Inverlussa, twenty-five miles from the dock at Feolin. The notorious Paps of Jura were shadows within cloud as we passed them, but the range of hills behind showed as a vast, jagged wall. We arrived at Inverlussa late in the afternoon. We were renting heather cottage for a week because of its relative nearness to Orwell’s Barnhill, and the whirlpool of Corryvrechan. The key was in the door. Inside, the living room was high ceilinged, clad in white-washed tongue-and-groove planks with a simple fireplace. The bookshelves contained genuinely readable books and local literature. The kitchen was small and well-equipped. I put the kettle on and hung our damp clothes above the fireplace on a clothes rack suspended by a pulley. We brought in our luggage and multiple bags of food and wine, almost enough for a week of good eating. I made a pot of tea. J went out to collect coal from the coal shed and engineer a makeshift barbecue. When I went to help and share wine, I found her lighting charcoal whilst suffering our first encounter with midges.

An example attack on an island further north…

My oily skin and blood-warm pate are an irresistible lure to all biting insects, let alone the insatiable midge. I couldn’t cope and retreated inside to rub cumin into lamb. Which reminds me:

http://www.buzzfeed.com/lukelewis/middle-class-problems?s=mobile

Soon, we were inside with the fire, eating char-grilled lamb steaks, halloumi, fresh made flat-breads, salad and red wine. Outside the window, highland cattle and deer crossed the bridge over the Lussa river and began to mooch around in front of the house. J and Rob surveyed the map to decide what we should do the next day. We would go to Ardlussa Bay.

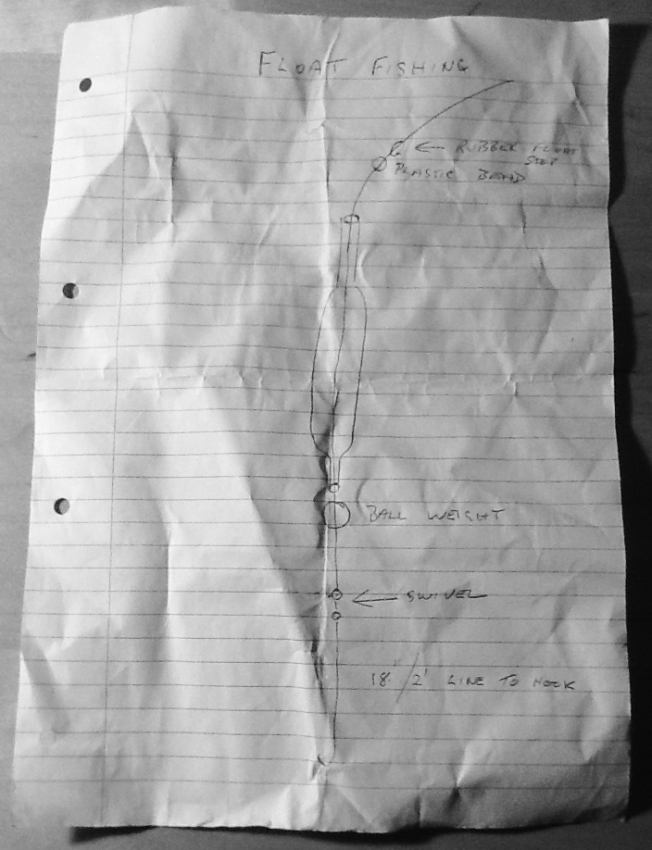

To get there, we walked back along the one road and through the Ardlussa estate. There were ancient stone outbuildings still in use, an open double door revealing a beautifully organised collection of tools and an alcove containing at least a hundred empty bottles of Jura whiskey. We brought a picnic with us, Rob had his Kindle, and I carried the beach casting rod I’d bought recently in Cornwall. The owner of the tackle shop there had promised me a lesson off Pendennis Point, Falmouth, but never showed. In the forty minutes I was in his shop, he had drawn for me some guides of how to set a line. Today, it was to be float fishing.

I prepared my line-as per the diagram- after breakfast to avoid fumbling on the beach.

I prepared my line-as per the diagram- after breakfast to avoid fumbling on the beach.

The sea at Ardlussa Bay is clear, you can easily follow occasional ribbons of seaweed-drifts to their roots in the shingle. After a while sitting, smoking, reading, Rob waded into the bay and swam eastward to a ridge of rocks four hundred yards away. There was a steady cross current, he made gradual progress. About twenty minutes later, he climbed out onto the rocks and was surprised when we pointed out several quite deep lacerations on his body, no doubt inflicted by the sharp shelving of the outcrop.

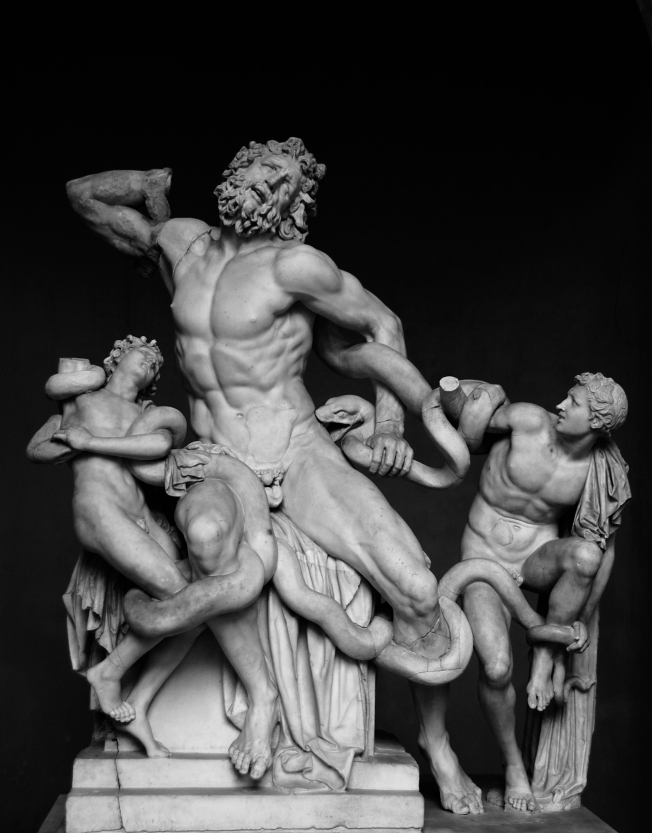

When we had first got to the bay, J and I ambled about, digging among the tiny pebbles, crab elements and sea-smoothed coal. I remember being acutely conscious that beach-combing should be a singular pursuit, yet J’s movements, always somehow in my periphery, beckoned me; today, I just wanted to be close to her. I found a small black rectangular stone with an exact white X across one of its faces. I gave it to her. We sat gently for some minutes before I headed around the north edge of the bay to find a fishing spot on a spit of rock that curved around the headland. The bay was fringed with yellow iris and tufts of marram that gave way to saturated grass as I walked upwards onto a sloping chase. There was a large paper target nailed to a wooden frame, splintered with rifle fire. I ducked behind and made my way through a narrow band of firs into dense rhododendron thicket. I plunged inside, rod in hand, threading myself ever deeper into a diabolical network of stone-hard rhododendron branches. I knew the others were expecting me to emerge onto the headland, and so pushed inwards toward what I knew would soon be the edge of a cliff. The trouble was, I had no idea where it would be, such was the density of the strange, semi-tropical foliage. I felt like Laocoon, hung in a three-dimensional game of Twister.

The leathery leaves thickened above me and blocked out the sun, my foot slipped and I dropped about ten feet directly down. Somehow, the rod stayed intact, but it was clear that I was now very much snared in this unnerving place. I was in the foundations of an old croft that must have stood on the coast here a hundred years ago. One of the walls remained, but the rest was granite-rubble, utterly subsumed within the monstrous organism. I felt very alone. Rob and J could only have been a quarter of a mile away, but I was by no means sure I’d be able to extract myself. I peered out at the sea through a tunnel of forked boughs; there, a few hundred yards out from the cliff, a small herd of seals were sunning themselves on a rock. The others had to see. There was no way I was staying here. I javelin-ed the rod through a gap above me and lunged upwards. I caught hold of a snaking limb, swung myself into the canopy, and painstakingly spider-ed my way through the endless loops. I was the end of a knotted piece of string, being drawn through one bight after another. After I finally escaped and stood in fresher air, I realised I had utterly lost my sense of time. I could have been fifteen minutes or an hour in that gloom. Looking back, the experience was uncannily like a recurring dream I used to have as a child. I was in the cellars of some vast industrial space. It was always dim and claustrophobic, there were innumerable hot water pipes and ducting, giant cogs smeared with grease, a cement floor and the faint humming of unseen machinery. I can’t have had this dream for at least twenty years but, back then, it would revisit me at least once every few weeks.

I walked back to the bay. J caught sight of me and strode to meet me. She didn’t know how glad I was to see her, how the sight of her gave me heart. We hugged. I probably pressed my face into the hollow above her clavicle. I told her about the seals and we decided to get to where we could view them by edging around the base of the cliffs. We managed this easily, I used the rod like a tightrope walker’s pole to balance along some of the sheer edges. We rounded a small inlet, then found we could peer across at the islets in the water. There they were, the herd of seals, still basking. It was clear the tide was rising and that soon they would be buoyed away. We skipped along the spit of land that narrowed into lively waves. After initially attaching my reel upside-down, I made ready for my first cast into Scottish waters.

I flicked the rod behind me, and flung it forward. The ball weight smacked miserably into the sea barely five metres from where I stood. Even worse, my line unspooled into wild coils that sprung rapidly outward, becoming instantly knotted. I was silently furious, embarrassed. I had a white and blue nautical shirt on, my best hat, decent kit- I looked the part. But now it was clear, I hadn’t a clue what I was doing. J came over, wordlessly. Her fingers deftly reordered the wire and wound it back around the reel, her fine hair brushed my face as the wind blew, calming me. Her hair and the line became, for a moment, indistinguishable. I cast again. This time, the float caught in the seaweed at the base of the rocks. J knelt and extricated it. Rob arrived from his swim, we marveled at his cuts, his endurance of the cold. While they both went to watch the seals, I cast again and again. I gradually improved, learning the gearing of the reel, which position to keep the bale in. My casts eventually reached about thirty yards. I caught nothing. When the seals were evicted from their rock by the tide, we made our way back around the edge of the shore. I swam out into the middle of the bay, taking in the amphitheatre of land about us. My head bobbed on the surface the way a seal’s does. I watched J curled on a rock in the sun, Rob had a cigarette. Time stalled a little. I returned to the shore, dried myself and lay against J’s warmth, anchored.

We walked a mile or so north on the road towards Lealt. There was a small cairn on a rise at the road’s edge. J observed: That is the least impressive cairn I’ve ever seen, it’s more like an elephant turd. The air became humid, the flora about us seemed to vary, as if we passed through shifting hemispheres. There were huge ferns, then weathered beeches; deforested slopes of burnt trees, then dense woods; moments of moorland and swift burns; countless mushrooms: slippery jacks, false chanterelles, an orange boletus. There were huge dragonflies. We turned back after admiring the coastline from a crumbling vantage point. Just before we descended to Inverlussa, we watched a herd of Whiteface Woodland sheep grazing. One particular sheep with jester-like, asymmetrical horns wandered across to a neighbour and pissed liberally on its head. Rob named him Crumplehorn and headed home.